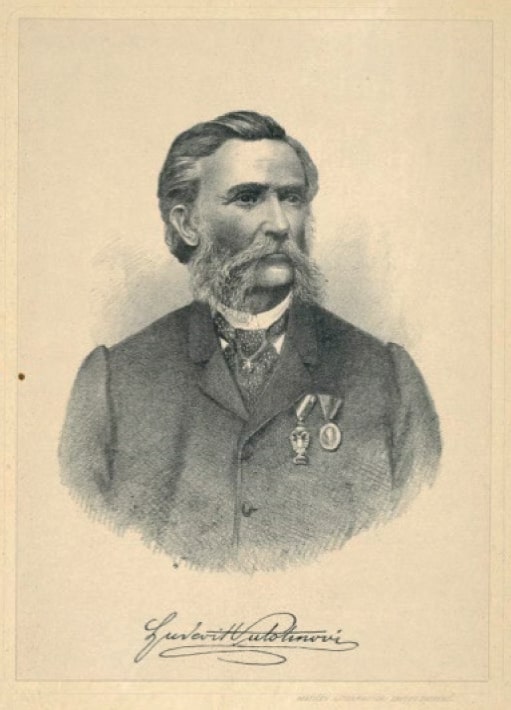

Ljudevit Vukotinović (1815 – 1893), a nobleman from the Farkaš family, also worked on creating Croatian mineralogical and petrographic terminology. In 1851, his extensive work "Mineralogia i geognosia" was published, in which he described in detail the principle behind the Mohs hardness scale and how it should be used. In this work, Vukotinović translated, described, and classified the names of around one hundred mineralogical terms and about two hundred petrographic terms.

1. TALK - ljuska mastikova prismatna

2. GIPS – euklas-solja prismatoidna

3. KALCIT – solja taljiva rhomboedrena

4. FLUORIT – solja taljiva octaedrena

5. APATIT – solja taljiva rhomboedrena

6. ORTOKLAS – iskrolistnik orthotomni

7. KREMEN – oblutak rhomboedreni

8. TOPAZ – topas prismatni

9. KORUND – korund rhomboedreni

10. DIJAMANT - demant octaedreni

1. TALK - ljuska mastikova prismatna

2. GIPS – euklas-solja prismatoidna

3. KALCIT – solja taljiva rhomboedrena

4. FLUORIT – solja taljiva octaedrena

5. APATIT – solja taljiva rhomboedrena

6. ORTOKLAS – iskrolistnik orthotomni

7. KREMEN – oblutak rhomboedreni

8. TOPAZ – topas prismatni

9. KORUND – korund rhomboedreni

10. DIJAMANT - demant octaedreni

Ljudevit Vukotinović was born in 1813 in Lovrečina to the noble Farkaš family. He completed his primary and secondary school education in Zagreb and Kanjiža, and his philosophy studies in Szombathely, today's Subotica. He studied law in Zagreb and Požun, today's Bratislava. While studying law in Požun, he became a jurat (lawyer) to Baron Ljudevit Bedeković, and from 1832 he was also a jurat to Count Janko Drašković, preparing himself for future political activity. From 1834 he served in various administrative and judicial positions in Banska Hrvatska. He passed the bar exam in 1836, after which he entered the civil service as a county notary in Križevci. In 1840, he became a grand judge in Moslavina County and continued his political and cultural activities. In accordance with Illyrian ideas, Ljudevit Farkaš changed his family name to Vukotinović in 1835, which was legalized in 1841. During the 1840s, Ljudevit Vukotinović devoted himself to pedagogical, state-legal, and socio-political issues, participating in the work of the Economic Society and the editorial board of the Gospodarski list. In 1847, he gave a speech in the Croatian Parliament about the need to introduce the Croatian language as the official language. This proposal was also supported by Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski. He was a permanent representative until 1854, and then he was retired because he opposed the introduction of the German language as the official language. In addition to all of the above, it is interesting to highlight the literary work of Ljudevit Vukotinović, which began in 1835 when he published the first Illyrian davoria, "Pěsma Horvatov vu Glogovi leto 1813," in the magazine Danica, known for the verse "Nek se hrusti šaka mala." Ljudevit Vukotinović died in 1893.